How does China's victory in 1945 still define the Taiwan question?

The Taiwan question arose when the Chinese nation was weak and divided, and it will be resolved when the Chinese nation's rejuvenation is complete.

Editor's note:

Hello and welcome to the "Big Argument" column, a distinctive commentary column in our newsletter that diverges from traditional Western narratives and perspectives. It focuses on hot-button issues that have yet to fully reflect the Chinese stance and perspective. Some notable pieces of the column, which are also among the most engaging articles in the history of this newsletter include Three key takeaways from latest Taiwan Strait military drills and Stabilizing U.S.-China relations: Trump can do it, if drawing lessons from past.

You might find that some views in the article differ from the typical Western perspectives, but I believe understanding different viewpoints might be one of the reasons some of you subscribe to this newsletter.

This year marks the 80th anniversary of the Allied victory in World War II and of the Chinese nation's triumph in the War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression. The victory carries extraordinary significance for the entire Chinese nation, as it was the first major victory China had achieved in a war of resistance against foreign aggression since the 19th century.

However, this victory of justice over evil and fairness over power has nevertheless been met with misguided questioning over facts, including Taiwan's restoration to China, a victorious outcome of WWII, and it was an integral part of the postwar international order.

On August 15, the anniversary of Japan's announcement of unconditional surrender 80 years ago, Taiwan leader Lai Ching-te publicly referred to it with the neutral phrase "end of the war," the same wording used by Japan, which seeks to whitewash its past aggression and ultimate defeat.

Lai's remarks blurred the fundamental line between justice and evil, between the victors and the defeated. In doing so, he has betrayed the Chinese nation that made immense sacrifices to end Japanese aggression.

This reveals a fundamental issue confronting the Chinese nation: the distortion of Taiwan's identity and status, which has shaped perceptions of both historical and current matters. This is known as the "Taiwan question."

To grasp why Taiwan has come to be seen as a "question," one must understand that, in the final stage of World War II, a series of documents of international law required Japan to return Taiwan to China. After winning the war in 1945, China had already restored its sovereignty over Taiwan. This was a consensus among the Allies, but Cold War divisions and geopolitics in recent years have obscured that reality for some—and even led to its outright denial.

1945: Taiwan comes home

In 1895, following its defeat in the Sino-Japanese War of 1894-1895, the Qing Dynasty government was forced to cede Taiwan and the Penghu Islands to Japan. However, people across the Taiwan Strait never stopped fighting to reclaim the island, carrying out successive waves of armed and unarmed resistance against Japanese occupation in and outside Taiwan.

But Japan's ambition extended far beyond Taiwan. In 1931, it invaded and occupied China's northeastern region, and six years later launched the full-scale war of aggression in the country. During the war of resistance, over 50,000 people in Taiwan went across the Strait to fight Japanese invaders. They held the belief that "to save Taiwan, one must first save the motherland."

Between 1895 and 1945, more than 600,000 Taiwan people died resisting Japanese rule, a powerful proof that the people of Taiwan, as an integral part of the Chinese nation, stood shoulder to shoulder with their compatriots on the mainland in the nation's darkest hour.

The dawn broke as the Allies joined forces to crush the Axis powers. In 1943, leaders of China, the United States and the United Kingdom met in Egypt, and stated in the Cairo Declaration that "all the territories Japan has stolen from the Chinese, such as Manchuria (Northeast China), Formosa (Taiwan), and The Pescadores (Penghu Islands), shall be restored to the Republic of China."

Chiang Kai-shek, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and Winston Churchill met at the Cairo Conference in Cairo, 25 November 1943.

The three Allied nations reaffirmed this term in their 1945 Potsdam Proclamation, which was endorsed by the Soviet Union shortly after, and accepted by Japan upon its surrender.

On Oct. 25, 1945, the Chinese government announced that it was resuming the exercise of sovereignty over Taiwan, and a ceremony to accept Japan's surrender in the Taiwan Province of the China war theater of the Allied Powers was held in Taipei. Days earlier, Chinese servicemen landed at the Port of Keelung. Their arrival was welcomed by millions of people across Taiwan.

Since then, China has recovered Taiwan, both de jure and de facto.

In September 1946, prominent figures from Taiwan, led by Lin Hsien-tang, traveled to the mainland to pay homage at the mausoleum of the Yellow Emperor, revered as the common ancestor of the Chinese nation.

This act proclaimed Taiwan's return to the big family of China, with Taiwan compatriots once again standing tall as proud Chinese.

That year, civil war broke out. After their defeat, the remnants of the Chinese Kuomintang (KMT) fled to Taiwan and entrenched themselves there. Across the Strait, on Oct. 1, 1949, the People's Republic of China (PRC) was founded.

The KMT regime had been overthrown, and the ROC was succeeded by the PRC, so that the Central People's Government in Beijing became the only legitimate government of all whole China. The process only involved the succession of the government, not the succession of the state. Thus, the PRC inherited the ROC's political power, its territory, and its international legal status. From the ROC to the PRC, the subject of international law -- China as a STATE -- did not change.

As a natural result, the PRC government enjoys and exercises China's full sovereignty, which includes its sovereignty over Taiwan, and Taiwan remains a part of its territory.

From clarity to contrived ambiguity

China's sovereignty over Taiwan ought to be an indisputable matter -- and was for years after 1949, had geopolitics not come into play.

The retreat of Chiang Kai-shek and his KMT remnants to Taiwan led to decades of confrontation across the Taiwan Strait. The 1950s saw repeated clashes across the Strait.

Even though the KMT claimed its regime -- rather than the central government in Beijing -- was the sole legal government representing China, both sides of the Strait recognized Taiwan as part of the Chinese territory.

To this day, no peace agreement or armistice has ever been signed between the two sides. The Chinese civil war that broke out in the 1940s has, in essence, not reached a definitive conclusion. The absence of such a formal arrangement has left the Strait in a special state of protracted political confrontation. This has been exploited by certain countries outside the region as a tool against China.

During the Korean War, or China's War to Resist U.S. Aggression and Aid Korea (1950-1953), the United States dramatically re-calibrated its strategic calculus and upgraded Taiwan's geopolitical value. In June 1950, shortly after the war broke out, U.S. President Harry Truman sent the Seventh Fleet into the Taiwan Strait and declared that the island's future must await "a peace settlement or UN consideration."

The phrase "status undetermined," an invention tailored by the United States and its allies to Cold War needs, laid the groundwork for the legal ambiguity that would soon follow.

The main prop was the so-called San Francisco Peace Treaty, also known as the Treaty of Peace with Japan, produced in September 1951. Drafted without the PRC, the sole legal government of China since 1949, the treaty recorded Japan's renunciation of Taiwan, yet named no recipient deliberately.

The fact that the treaty was drafted and signed behind China's back was a blatant breach of postwar legal norms. As per the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, a treaty does not create either obligations or rights for a third State without its consent. In other words, a treaty signed without China's involvement has no authority to determine the future of Chinese territory.

Notably, the KMT was not invited to the San Francisco conference either.

In addition, as a major Allied Power that joined the war against Japan in 1945, the Soviet Union did not sign the treaty. While they participated in the conference, their delegation strongly opposed the treaty's terms.

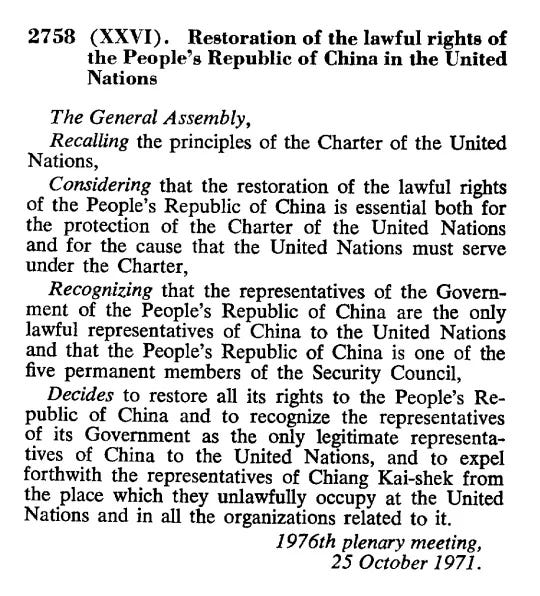

On Oct. 25, 1971, the 26th session of the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) explicitly rejected proposals for "Two Chinas" and "Taiwan self-determination." The UNGA Resolution 2758 was adopted with an overwhelming majority, expelling the representatives of Chiang Kai-shek, i.e., the representatives of the KMT regime in Taiwan, from the place which they unlawfully occupied at the United Nations and restoring all its rights to the PRC.

The resolution was unequivocal: the two words, "RESTORE" and "OCCUPY," meant that the UN recognized that the PRC succeeded the ROC as the sole representative of all China since 1949. Thus, the seat of China in the United Nations has always represented the entirety of China, including Taiwan.

On the day of the vote on Resolution 2758, Chiang Kai-shek's representative also acknowledged in a statement that other countries "have stressed the fact that Taiwan is Chinese territory," "on this I cannot agree more..." and "the people of Taiwan are Chinese in terms of race, history and culture."

The "undetermined status" thesis, born of Cold War maneuvering, had no legitimacy except in the narrative of Taiwan secessionists.

Eighty years on: Why the record matters

The Taiwan question sits at the core of China's core national interests, and the one-China principle is the political foundation and a fundamental premise upheld by the People's Republic of China when establishing diplomatic relations with other countries.

The most important content of this principle is that there is only one China in the world, and Taiwan is an inalienable part of the Chinese territory.

As China has established diplomatic ties with over 180 countries in the world, the one-China principle has become the widely recognized consensus of the international community.

However, China's continued rise has caused unease among some Western nations still clinging to a Cold War mentality, leading their policies toward China to increasingly favor containment over engagement. Thus, the Taiwan issue has become a strategic leverage point for counterbalancing China.

In particular, the United States deliberately maintains ambiguity on the Taiwan question -- the so-called "strategic ambiguity" -- seeking to constrain China politically, economically, and militarily.

In recent years, from massive arms deals to high-profile visits to Taiwan by politicians such as Nancy Pelosi, as well as repeated "stopovers" by Taiwan leaders, the United States has been hollowing out the one-China principle, sending wrong signals to secessionists on the island and blurring that principle in the eyes of the world.

On the other hand, with drastic changes in Taiwan's political landscape since the late 1980s, the secessionists, especially the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), seized the chance to push ahead with their independence agenda. One major campaign is to rewrite the history of Taiwan, including its restoration to China in 1945. It also refuses to recognize the 1992 Consensus, which embodies the one-China principle.

Oct. 25 was a public holiday in Taiwan to celebrate its restoration to China until it was canceled in 2001 by the DPP authorities. Since the DPP took office again in 2016, the authorities have halted commemorative activities, leading to a gradual fading of public memory -- particularly among Taiwan's younger generation.

While the United States and Taiwan's secessionist-minded authorities repeatedly tampered with the historical narrative of Taiwan's restoration to China, Beijing has upheld the facts with consistency and clarity.

China will hold activities around Oct. 25 to mark the 80th anniversary of Taiwan's restoration to China from Japanese occupation, as part of the events for the 80th anniversary of the victory in the Chinese People's War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression and the World Anti-Fascist War.

The anniversary is more than commemoration. It is a reminder that the Taiwan question arose when the Chinese nation was weak and divided, and it will be resolved when the Chinese nation's rejuvenation is complete.

Remembering China's victory in 1945 affirms that whatever turbulence arises in Taiwan's political landscape, and whatever meddling comes from outside, China's reunification remains certain. It is an essential part of national rejuvenation.

The only question that remains is how.