Inside China’s 7.48 million ride-hailing drivers

What a landmark report reveals about flexible employment in a changing economy

Lately, as my foot continues to recover and I can’t walk much, I’ve been commuting by ride-hailing almost every day. These daily rides often turn into conversations with drivers — about their lives, recent events in China, or even the pros and cons of different electric vehicle brands (most ride-hailing cars here are now EVs. If you’d like to explore China’s EVs further, you can read my three recent newsletters summarizing Luo Yonghao’s interviews on China’s electric vehicle sector).

Against the backdrop of economic headwinds and structural shifts, ride-hailing has become an important employment buffer in China. By 2024, the number of licensed ride-hailing drivers nationwide had reached 7.48 million — a figure roughly equal to the entire population of Hong Kong. Earlier this month, the China Research Center on New Forms of Employment (CNFE) released a comprehensive report on the country’s ride-hailing workforce. The study draws on 5,417 questionnaires collected from drivers across 13 provincial-level regions in July 2025, supplemented with big data analysis and in-depth interviews.

The findings paint a detailed picture of this rapidly growing labor group. According to the report, 62.8 percent of drivers are the sole breadwinners in their families, 77 percent entered the profession after losing a previous job, and 7.4 percent are recent graduates from 2024 onwards. The average driver is around 40 years old, and men make up the overwhelming majority. The report also compares ride-hailing drivers with other blue-collar occupations, including delivery workers, truck drivers, couriers, manufacturing production workers, and construction workers.

As China’s economy develops and transforms, a vast number of flexible jobs have emerged — and the profile of these workers deserves closer attention. This report, I believe, offers one of the most comprehensive looks to date. That’s why I’ve chosen to share its highlights here. The highlights are based in part on Caixin’s reporting and CNFE’s WeChat blog on this report. I have also uploaded the full Chinese text of the report to Google Drive, where you can download it.

About CNFE

The China Research Center on New Forms of Employment (CNFE) (中国新就业形态研究中心) was jointly launched by Capital University of Economics and Business and China Association of Employment Promotion (CAEP), with the aim of advancing both theoretical and empirical research on new employment patterns and providing evidence-based analysis for policymakers. The center is operated by Capital University of Economics and Business under the guidance of the CAEP, a nationwide nonprofit organization established in 1993 under the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security.

The report points out that China’s online ride-hailing sector has surged in the past decade, offering numerous low barrier to entry level employment opportunities to individuals experiencing unemployment or having to find another job. It has also served as an employment stabilizer in regions facing employment pressures. Compared to other blue-collar professions, online ride-hailing drivers enjoy certain advantages in terms of job autonomy, income, and satisfaction.

However, the report cautions that the sector faces development hurdles amid an economic slowdown. In 2024, the number of certified online ride-hailing drivers in China reached 7,483,000, a substantial increase of 159 percent from 2020. This surging supply contrasted with a mere 38.3 percent rise in the number of monthly average orders. These issues, alongside fiercer industry competition, demanding working hours, and insufficient social security benefits, continue to challenge the employment quality for this emerging blue-collar demographic.

The report reveals that online ride-hailing drivers are predominantly middle-aged. The average age of surveyed drivers is around 40, and males are the overwhelming majority. Citing data from the China mobile internet database, the report notes that in April 2025, “Didi Driver” was the top-ranked app for males aged 31-45, indicating that a significant number of middle-aged men depend on the Didi online ride-hailing platform for their livelihood.

Female online ride-hailing drivers represent less than 10 percent, but their proportion is growing annually. The “2025 Didi Digital Mobility Female Ecosystem Report” shows that in 2024, over 1.5 million women globally generated income through Didi. More than 1.05 million of these were in China, where 79 percent of them were the sole income providers for their households.

Another notable demographic trend is the growing presence of older individuals in online ride-hailing. The report’s survey data reveals that the average age of online ride-hailing drivers stands at 39.8 years, aligning closely with the average age of China’s workforce. While male drivers aged over 55 represent 2.4 percent, female drivers over 50 constitute a greater proportion at 10.2 percent.

Against the backdrop of a phased increase in the statutory retirement age, online ride-hailing is becoming a new avenue for some older individuals to achieve a “semi-retirement” or flexible work-life balance. The report notes that more than 20 cities, such as Hangzhou, Chengdu, Kunming, Shenzhen, Qingdao, and Weifang, have now raised the maximum registration age for online ride-hailing drivers to 65.

The report highlights that for middle-aged drivers, the backbone of the online ride-hailing sector, this job plays a unique role in meeting urgent employment needs and providing a “safety net” for families struggling to make ends meet.

More than half of the surveyed drivers, 62.8 percent, are the sole or primary contributors to household income, while 77 percent of them have transitioned into the sector after being displaced, meaning their families are under immense financial pressure.

Drivers come from a variety of previous professions. The report indicates that nearly 70 percent hailed from traditional blue-collar sectors like manufacturing, construction, and catering. Some others were individuals who had experienced entrepreneurial failure or had previously run their own businesses. They might have transitioned into the sector due to different reasons, such as layoffs, pay cuts, and entrepreneurial setbacks. Yet, a common thread unites them: the ride-hailing sector offers immediate payment, low entry requirements, and flexible working hours, providing a vital employment buffer that allows them to quickly resume earning and balance family responsibilities.

Despite the huge base of drivers, the report mentions, less than 30 percent are highly active — those who consistently log on and remain available for ride requests. This suggests that the remaining drivers function more as “part-time” workers, flexibly juggling their work with family responsibilities.

Notably, the surveyed sample included veterans at 13.2 percent and recent college graduates (from 2024 onwards) at 7.4 percent. Both groups, the report notes, commonly encounter frictional unemployment and are in need of a low-cost, low-barrier “transitional position” to ease their move to the next stage. This is precisely the kind of opportunity that becoming an online ride-hailing driver can offer.

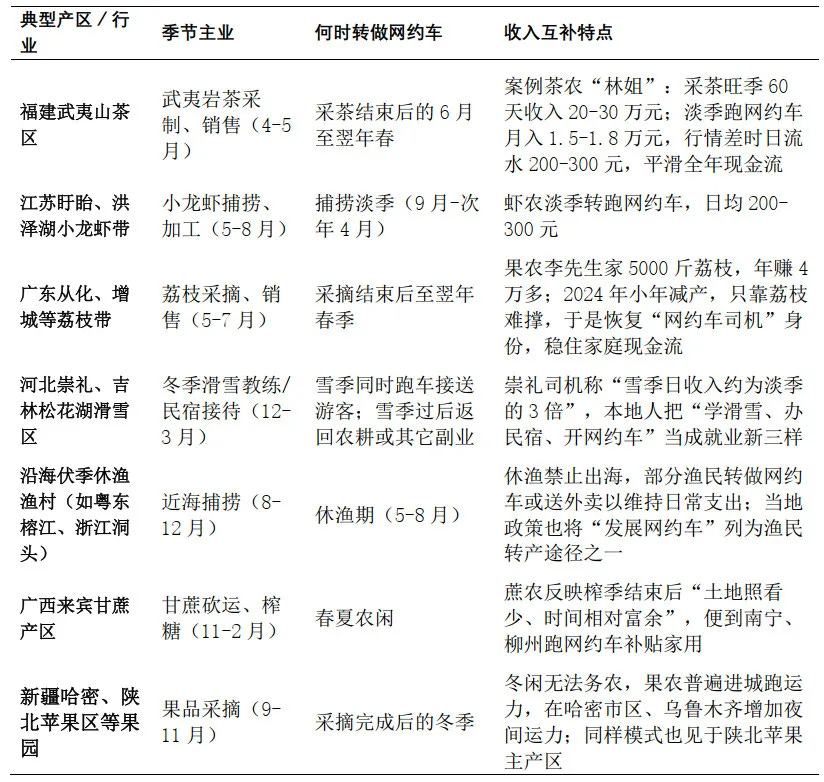

In regions experiencing industrial relocation and upgrading or fluctuations in foreign trade, the online ride-hailing sector serves as an anchor, helping to stabilize employment. In the same vein, it serves to cover income shortfalls for workers affected by industry downturns or seasonal employment, filling the “off-season” income vacuum.

To illustrate, the report cites the efforts to cut overcapacity in the steel and coal sectors from 2014 to 2019. According to estimates by China’s Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security (MOHRSS), roughly 1.8 million employees were part of this relocation and resettlement process, primarily male workers aged 40 to 50. Characteristically, they had a narrow range of skills that hindered inter-industry mobility and bore heavy family burdens.

According to Caixin, Zhang Chenggang, director of the research center for new forms of employment and an associate professor at the Capital University of Economics and Business, investigated the impact of new forms of employment on the reemployment of workers displaced by overcapacity reduction. His findings revealed that by June 2017, 352,000 steel and coal workers had transitioned to the Didi platform, making up 19.6 percent of the 1.8 million.

The report also compares online ride-hailing drivers with other typical blue-collar professions, including delivery workers, truck drivers, couriers, manufacturing production workers, and construction workers.

Data shows that online ride-hailing drivers earn an average monthly income of 7,623 yuan (about 1,072 U.S. dollars), trailing only truck drivers (8,424 yuan). This figure is markedly higher than that of delivery workers (7,496 yuan), couriers (6,124 yuan), as well as manufacturing production workers and construction workers (5,900 yuan). Geographically, highly active drivers in first-tier cities earn more: an average of over eight hours online daily (with 5.1 hours on average spent on actual deliveries) can yield a monthly income of 11,557 yuan, exceeding the monthly average disposable income (7,705 yuan) for Beijing’s urban residents in 2024.

Currently, online ride-hailing drivers report an income satisfaction rate of 81.4 percent, significantly higher than truck drivers (21.95 percent) and delivery workers (64 percent), placing them first among blue-collar workers. The report attributes this to three key factors: firstly, a relatively comfortable working environment that avoids exposure to extreme heat and cold; secondly, timely settlements leading to strong cash flow; and thirdly, a more equal labor relationship, where drivers have the right to refuse orders and appeal negative ratings, thereby safeguarding their professional dignity.

In terms of career development, online ride-hailing drivers have the highest safety training coverage at 95 percent and a retention intention of 75.7 percent, both the highest among blue-collar groups. In comparison, delivery workers’ retention intention stands at 68.4 percent, while for truck drivers and construction workers, it is less than half.

However, the report points out that the current online ride-hailing market is experiencing capacity saturation and slowing order growth. Although platforms like Didi are implementing measures such as “transparent billing,” reduced commissions, and diversified subsidies to help drivers maintain stable incomes, the overall industry imbalance between supply and demand, leading to price competition and declining earnings, still poses a core challenge to driver satisfaction.

Citing data from the MOHRSS, it notes that by 2024, there were 7,483,000 licensed drivers nationwide, a whopping 159 percent increase since 2020. The substantial increase in the supply of drivers contrasted with a mere 38.3 percent rise in the number of monthly average orders.

Simultaneously, multiple platforms engage in price wars, leading to a decrease in order prices. To achieve their target income, drivers are compelled to extend their working hours. The report’s survey indicates an average daily online time of 6.41 hours for drivers, with a peak distribution around 10 hours.

[Editor’s note: Since July, several local governments across China have rolled out policies to tighten regulation of ride-hailing trips with upfront pricing and curb cut-price competition.”

Platform commissions are also an important factor affecting drivers’ perception of their income. Survey samples show that the average monthly commission rate for drivers is 18.9 percent, with a median of 18.8 percent. While commissions show little fluctuation, driver perceptions vary considerably. The report analyzes that despite Didi's launch of “transparent billing,” allowing drivers to view commission rates in real-time, certain online communities and discussions have fostered an impression of “excessively high commissions.” Combined with the seasonal fluctuations in subsidies, this amplifies negative perceptions.

Furthermore, due to intense industry competition, some car rental companies have ceased operations, and smaller platforms have exited the market, resulting in financial losses for some drivers. Beyond internal competition, some cities have seen traditional taxis squeezing out ride-hailing services, with restrictions on operating zones, pricing, or apparent bias-based policing. Some drivers, facing insufficient order volumes, have transitioned to part-time work or even re-entered unstable employment cycles.

Insufficient social security coverage is another concern. The survey indicates that only 10.5 percent of online ride-hailing drivers contribute to basic old-age insurance and medical insurance for urban employees, remarkably lower than construction workers (41.2 percent) and truck drivers (32.24 percent). While the Didi platform offers supplementary insurance through programs like the “Didi Driver Protection Plan” and “Didi Guanhuaibao,” the overall participation rate remains inadequate, leaving long-term occupational safety without systematic support.

The report concludes that ride-hailing work excels in terms of income flexibility (a mix of fixed and variable remuneration), work-life flexibility, and growth and career opportunities, though the formalization of social security benefits remains an area for improvement. It states that a key policy challenge for the future is how to explore more inclusive and sustainable social security solutions, for example, promoting the integration of commercial insurance with basic social security, that do not stifle the vitality of flexible employment, thereby bridging the protection gap for flexible workers.

Quite interesting to compare against Malaysia (population 35 million) where there are 1.6 million gig workers - mostly in ride hailing or delivery.

So Malaysia is about 1/350 of China's population but approx 1/5 of gig workers