Short videos, mortality, and cats: Wang Shuo at 66

"Now everyone says AI will replace all jobs and everyone will just stay home. I actually think that's when literature and art will revive."

Good afternoon. Today, I want to introduce you to a newly released interview with one of the most subversive — and controversial — figures in contemporary Chinese literature: Wang Shuo (王朔). Wang recently gave his first on-camera interview in 18 years, speaking with The New World (新世相), a widely followed digital media platform in China.

Some overseas China watchers may not be familiar with Wang Shuo — and that’s perfectly understandable. For much of the past two decades, he has kept a remarkably low profile, retreating from public view even as his influence quietly endured. To help bridge the gap, I asked DeepSeek to generate a brief three-paragraph introduction to Wang Shuo for international readers — followed by my own thoughts on why this rare interview is worth your time.

1. Literary Style and Breakthrough: Wang Shuo is one of the most subversive writers in contemporary Chinese literature, known for his razor-sharp wit and irreverent storytelling that shattered the solemn conventions of traditional literature. Works like Wild Beast (动物凶猛) and The Troubleshooters (顽主) depict the lives of ordinary people and social outcasts, deconstructing grand narratives while exposing the absurdity and restlessness of post-reform China. His so-called "hooligan literature" (pizi wenxue) not only challenged the then-mainstream thought but also reinvigorated Chinese writing, making him a pioneer of avant-garde fiction.

2. Social Critique and Cultural Impact: Wang’s writing is fiercely critical, satirizing bureaucracy, moral hypocrisy, and materialism—all of which reflected the spiritual crisis of a society in transition. His novels and essays served as a mirror, capturing the confusion and struggles of everyday people amid China’s market economy boom. This rebellious "Wang Shuo spirit" influenced an entire generation and even permeated pop culture (e.g., the TV series Stories of an Editorial Board), becoming a defining phenomenon in 1990s China.

3. Controversy and Legacy: Though controversial for his "desecration of the sacred," Wang revolutionized Chinese literary language by elevating Beijing slang, dark humor, and colloquial rawness into high art. His work inspired later writers and artists (e.g., Wang Xiaobo, Feng Xiaogang) and forced society to confront the line between authenticity and pretense. Today, Wang Shuo is recognized not just as a literary rebel but as a keen chronicler of China’s social transformation—whose value lies precisely in his "untimely" honesty.

My Personal Take: If you're hoping for commentary on geopolitics or current affairs from Wang's interview after nearly two decades of silence, you’ll likely be disappointed. This interview isn’t about that. Instead, Wang reflects on his daily life, his fondness for scrolling short videos, what cats have taught him about mortality, why he still writes, and what led to his latest long novel series, In the Beginning (起初).

Wang Shuo — and the cultural moment he represented in the 1990s — is inseparable from the stories of China’s social transformation during the early years of reform and opening-up. His writing captures the raw emotion of that era — the anxiety, confusion, excitement, and struggle — all filtered through the lens of ordinary people.

To understand China, one need not always start with diplomacy, China-U.S. relations, or the Taiwan question. Sometimes, the most revealing insights come from voices like Wang’s — not because they are trying to “explain China” to the world, but precisely because they aren’t. Wang Shuo may not be speaking to an international audience in this interview, but if you're interested in China, he’s absolutely worth listening to.

The New World‘s Interview — Wang Shuo: I Swore I'd Never Live Past 40, Now I'm Almost 70

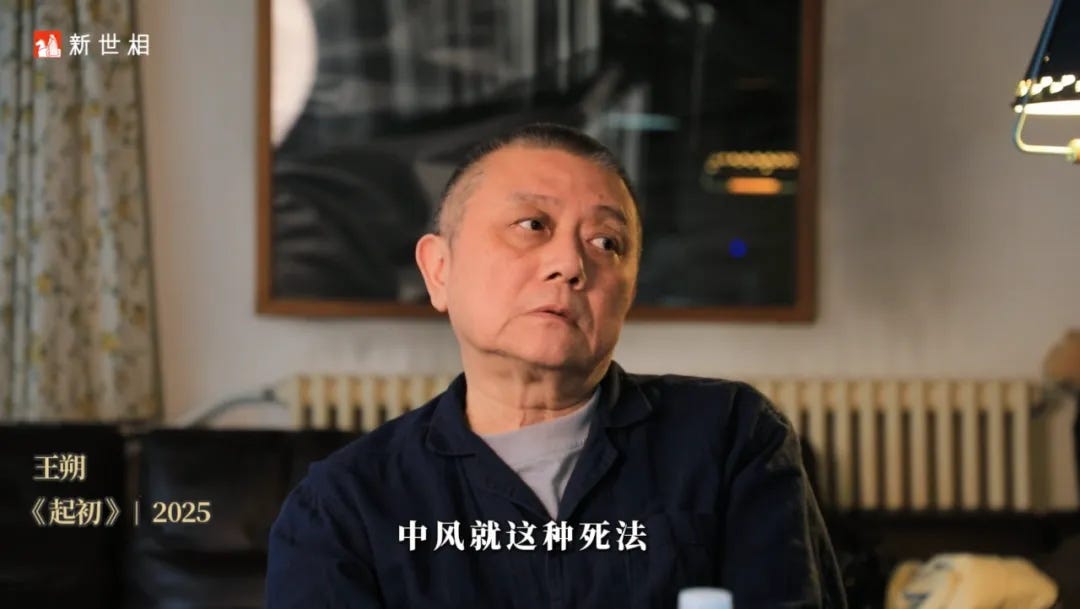

Wang Shuo's last video interview was eighteen years ago, and this is now. In The New World interview, we asked Wang Shuo 10 questions.

After watching the interview video and reading the text, compare it with this official summary from his TV appearance 18 years ago, and you'll see how he's changed: "Renowned writer Wang Shuo graced the major talk show 'Phoenix Salon,' pontificating and passing judgment on others, still maintaining his persona, cursing as soon as he sat down. Besides expressing disdain for certain figures' remarks, he harshly criticized various literary figures."

Wang Shuo in the "Phoenix Salon" interview in 2007

After that, Wang Shuo went into seclusion for over a decade. The only thing that emerged was a written report published in Southern People Weekly in 2015. Through it, people learned that Wang Shuo had cats—one named Duoduo, another named Babu; learned about his daily life, making himself a pizza-style flatbread for breakfast with extra cheese for nutrition; learned he was immersed in writing, planning to write three to four hundred thousand words, saying "Whether it gets published or where it gets published doesn't matter—as long as it comes out before I die."

Looking back now, that novel was "In the Beginning," a massive 1.4 million words, with the first volume published in 2022. The story is no longer set in contemporary Beijing but spans from the battles between the Yan and Yellow Emperors to the Western Han Dynasty. He says he's talkative and wants to get his words out—that's what the novel is written for.

It was because of this book series that The New World got the opportunity to interview Wang Shuo. We sent 10 questions to Wang Shuo through the editorial department of "In the Beginning" and received the following responses.

Below is Wang Shuo's latest interview transcript from the 2025 The New World interview.

Wang Shuo: Chatting like this is fine. If there were a bunch of strangers below, I couldn't do it. When people come to my place, I'm on home turf. If it's unfamiliar territory, I'm actually on guard.

I've been scrolling short videos for ten hours a day recently. It's driving me crazy—my vision's getting worse, my dry eye is acting up, I'm sick of it. I'm planning to quit these short videos.

It's all just mindless scrolling out of boredom, and now I can't focus on anything. I think I should read a book, but then I think, maybe just scroll a bit? And boom—an hour's gone.

I like watching history, military stuff, and military history. There are some internet-famous cats I always follow. I also watch cooking videos—Western baking, and dishes I eat myself like mashed potatoes with cheese and eggs. I don't make anything that complicated, but I like watching them fuss around kneading dough forever. There are some who make flatbread—brush on oil, knead the dough, add shortening, and the bread stays soft forever.

There's one dish I really want to eat just from watching, but I won't—it's this place in Chengdu called Laoma's Pork Trotters. The trotters are stewed until white, the skin stretching as they're placed in a bowl of red sauce. Watching them slurp it down...

When I'm writing, if I wake up at midnight I can't fall back asleep. I have to come out and write for two hours before going back to bed. I used to drink tea, but sometimes I really couldn't sleep when I went back, so now I don't drink tea anymore. I recently discovered my uric acid—I have gout—suddenly dropped by over a hundred. I wondered what happened, and it's because I stopped drinking tea.

I still cook every day. Let me tell you, the foolproof dish is ground meat stir-fried with anything. The heat requirements aren't strict—just cook it through, add soy sauce instead of salt and it won't be too salty. Now because my blood lipids are high and I have serious metabolic issues, I'm eating steamed vegetables. I couldn't have imagined it before—steamed vegetables with a splash of soy sauce. Oh man, it's so bland.

I vacuum too. While vacuuming I think about all sorts of random things, and often I can think them through. It's like when you're driving and thinking—new words pop into your head.

I try to handle every detail of daily life myself. When writing, there are many gaps between plot points that need details to fill them. Without life details, it's all too dry. But if you're not writing, I suggest don't do housework either—better to go out and play, find people to chat with over tea.

I originally had a place where I wanted to die, but then I thought, forget it, I'll die here. Because I never considered getting sick—you have to see doctors, have to speak clearly with people.

So I'll die here, die in this house. My daughter says don't die in the house—it'll be hard to sell. Hahaha. I figure it'll definitely be cardiovascular, a stroke, that kind of death.

My own cats, sixteen and seventeen years old—one had mammary cancer, one hyperthyroidism, both died. I'd raised them for over a decade. I haven't been with any person for that long. There are over a dozen cats buried in my yard, though I didn't raise all of them to death—some died and were buried here.

I'm not sad, I feel for them... because I think all beings suffer in this world. There's nothing worth clinging to in life—what's so good about it? Life is just what it is. I think I'll learn from them in the future, face death bravely, not shamelessly cling to life. Be clean about it—cats die very cleanly. They can really endure pain. I think that's remarkable.

Why are you so superstitious? You're afraid to talk about this. Is it heavy? Not heavy at all. I'm almost seventy—I think talking about this is perfectly fine.

A lifetime passes especially quickly, in the blink of an eye, really just a blink. Actually the slowest part is the first thirty years. After forty, each decade flies by. Before you know it, how did fifty become sixty?

When I was young, I thought forty was really old. I made pacts with people saying I absolutely wouldn't live past forty, yet here I am, shamelessly living past forty. You know back then many old people were particularly shameless, going around writing inscriptions for people, attending all sorts of random meetings—there were groups organizing meetings with various people. I thought when I got old I absolutely couldn't be like that, and after getting old I shouldn't show my face anymore—who wants to see your old face? Haha.

When I was young I liked cloudy days and light rain. Back then I'd see old men leaning against walls—what were they doing? Later I discovered you really do need to lean against walls. After sixty you really need to bask in the sun. Life's destination is the corner by the wall. All my recent social gatherings are with seventy-year-olds—people in their eighties have started appearing.

To be honest, aging hasn't changed me much psychologically. There's a mirror in my house where I still look young. But I really want to take a photo of myself in that mirror to see if I'm hallucinating. It's very strange—in that mirror I don't age, but in other mirrors I look old.

When we were kids there was a food called stinky Chinese toon. It still exists, but I've never eaten it. At my age, I won't eat things I haven't tried, won't meet people I haven't met. Life can just continue as it is, right?

Young people today have a lot of pressure. Back in our day it was even more uncertain. In 1980, society had just begun transforming. I was probably a bit carefree then. The jobs back then sound like nothing now—earning just over 30 yuan a month, barely enough for food, but there was no pressure.

Everyone lived in cramped spaces then—families of four or five in one room. There was no real estate market. When someone's kid grew up and got married after returning from the countryside, they'd build a tiny 5-square-meter room inside.

The key was the wealth gap wasn't big then, so no one made you angry. These short videos make you angry every day—your sense of unfairness is especially strong.

Back then you could still look down on households with ten thousand yuan—they were all just released from prison, not good people. The richest person made ten thousand yuan, and we thought if you made ten thousand you could retire.

The other day in conversation, someone asked if I'd want to go back to being young. I definitely wouldn't. If I went back now I couldn't handle it. Living from the beginning is too exhausting. Even if you don't worry about money, starting over is too tiring—dealing with people of all ages, managing various relationships with family, parents, wife, kids. Too exhausting.

A couple days ago someone asked if my life has been pretty smooth. I thought about it for a while and had to admit I've had a pretty smooth life. Nothing major has happened to me. Everything that's happened I did myself, and I own up to it. What I did myself never got out of control—it was basically within my ability to manage. So I've been able to preserve my personality until now, like it says in "Nine Stories"—try to preserve your nature. Actually every era has people who sail through smoothly. People shouldn't be tortured. That stuff about suffering builds character? Bullshit.

There's nothing I really want to do in this life anymore. I'm not curious about the world anymore. The world is what it is, nothing new.

The editors from my time were all older—I considered them teachers. Now you all, to me you're all kids. Hey, do you think editors won't be needed in the future? In how many years will print disappear, right?

Now everyone says AI will replace all jobs and everyone will just stay home. I actually think that's when literature and art will revive. Either you'll film things yourself or write things—you'll still need platforms for electronic versions.

Screenwriters already have an AI platform producing scripts. But complete personalization still doesn't work, and think about it—it's fed existing material. If academic papers check for plagiarism, when you ask it to write scenes, won't it plagiarize?

Of course I think eventually you'll give AI ideas, because writing has technical aspects—let it handle the technical completion, collaborate with it to write. I think that works. So then it'll all be about pure skill, relying on traffic for money. That's how it'll be in a hundred years, right?

What would I want to say to my younger self? I don't want to talk to him—he wouldn't understand anything I'd say.

We were dumber then than you are now. At least you have more information. Back then I really wondered if everything had already been written.

Before 1980, China didn't really have the concept of writers—writers were either old or dead. Actually the vastness of writing means no matter how many people came before you, there's still space for you.

I started writing in '79 when I was in the army—that was scar literature. Today it's embarrassing to say which writers you liked back then.

I'd just been drafted, and because I got terribly seasick, I was sent to a warehouse on land as a medic. There was nothing to do—I was just idle. You know back then there was no TV, no movies, no pop songs—only novels and poetry. Bei Dao, Gu Cheng, these people were like rock stars. When they went to universities, students went crazy.

And writing fiction could change your fate—win an award for a short story and boom, you'd be transferred to a professional department with a proper position. Of course I wasn't after that—not that I wasn't, I just didn't dare think about it.

There weren't many novels then. Each one published caused a sensation, everyone read each one. After reading them, an arrogant thought arose in me: Just this? I can do this too. Written like this?

When I said "I can write this too," I meant written this badly, I can write. I think writing requires strong confidence. I've met many smart people without confidence, and they have this mistaken idea that they have to write well before showing it—operationally they hold themselves back.

The young Wang Shuo

When I was in the army I wrote a story. Back then soldiers only had one magazine—"PLA Literature and Art." I sent it there and hey, they published it. Back then editors would even revise your work. My story was maybe three to five thousand words, and the editor revised fifteen hundred or two thousand words and published it.

In our unit, a grassroots unit, that was an incredible thing. The General Political Department called, and they transferred me to Beijing to review manuscripts. That left an impression—with my bit of cleverness, if I really had no other way, I could make a living from this. So I just kept writing randomly.

Back then we didn't talk about literature among ourselves, just chatted randomly. There were many writers' gatherings, but we just played cards together.

Let me tell you, most writers themselves are particularly boring. A truly extroverted person can't be this kind of writer. Most don't say much—playing cards together can get awkward. Everyone can only pretend to chat sincerely, but how long can that last?

Back then there were old writers who loved holding exchange meetings. I attended a few—pretty pointless. Mostly surface talk—what could they say? Literature is something you understand through your own experience. Where you're weak, you're weak—you can't change it, you can't get past it. For most people, just read their work. The work is them.

The writers who influenced me most—I had them back then, but now I'm ashamed to admit it.

Many authors I liked, I later saw through their flaws. When I read, I always look for their weaknesses. Really, all novels have flaws, none are perfect. When I see the flaws I stop reading—when I see them straining, showing weakness, I feel I've understood this person.

When I was young I especially liked two people—Hemingway and Remarque. When I saw Hemingway's telegraph style, that "Farewell to Arms," having a romance with a nurse—we'd all done that, I was a medic, haha. Actually I haven't completely seen through these two yet. Hemingway's macho posturing at the end showed some cracks. I think "The Old Man and the Sea" isn't good—I don't like that kind of thing. But he really did survive plane crashes, two or three times, he really did it. But that's fake machismo—I don't like it.

Wang Shuo in his study

A couple days ago I read about some Greek poet who supposedly removed all literary decoration and only stated facts, influencing people like Brodsky and a bunch of others. I bought a copy, and one poem really disgusted me—about being a Greek in a Greek palace seeing all this glory, Byzantine splendor, feeling especially proud. I thought, what does imperial glory have to do with you? Is this nobility? This is just taking imperial glory as your own glory. I immediately disliked this person.

I think leaving your name for posterity is delusion. Among those who've achieved immortality, I think most aren't that remarkable. Take those thunderously famous 18th-century works we read as kids, that critical realism, Tolstoy and such—you can't read them now. What rambling stuff—it's all period-specific.

In China, only a few can truly be immortal. Qu Yuan might last, but honestly, after millennia not that many people read him—students have to for coursework. The "Dao De Jing," "Analects," "Great Learning," "Doctrine of the Mean"—all just a few thousand characters. Can they last another ten thousand years? After ten thousand years, few people will even know Chinese, let alone classical Chinese.

As a kid I read the section about Emperor Wu in "Comprehensive Mirror in Aid of Governance." When I grew up and returned to the book, that section became the most familiar to me. As for myself, I don't think there's any need to write about my own life anymore, but I have things to say, so I'll just say them through other people.

I originally thought writing about emperors wasn't a good idea because emperors are easily reduced to concepts, especially famous ones like Emperor Wu. I wasn't sure how to write it at the time. Then I read Joseph Heller's "God Knows." Back then I still had some... a prostrate feeling toward history and emperors—not prostrate, maybe half-kneeling, thinking history was great and imperial achievements glorious.

Then when I first read "God Knows"—written like that, making King David so messed up. That shattered some things in my mind.

I think emperors and generals come from the people—they're essentially common folk. They're not that great, their minds aren't that sharp. It's those fake loyal ministers below, those bastards giving them terrible advice, creating lots of absurd situations. Actually, just write them as ordinary people—that's how I reconciled with myself.

“In the Beginning” long novel series

Looking at my writing "In the Beginning," I'd say I wrote from middle age to old age. In middle age there was more playful writing, but toward the end it became increasingly serious.

When I was younger I also thought about making money through writing—that's normal. Writing is a craft, and practice makes perfect. Money-making books are formulaic, following patterns—you really don't need to put yourself into those, you can write them by learning techniques.

But writing is multifaceted. Some people don't write for money—they transition from writing for money to writing for themselves. Actually many people stop writing when they can't make money. Many of my contemporaries changed careers, went into business.

Different ages bring different choices. When you write for others, you actually need to cater to them. Writing for yourself is more comfortable. I don't think there's much difference in quality. Those who make lots of money—great. Those who don't make money, who write especially for themselves—once it's written, the goal is achieved. In the end, people can only live for themselves, right?

I think literary talent is daydreaming. There's nothing to discuss about real life—everyone lives mechanically. Only the habit of daydreaming is interesting.

Writing it out is like putting what's in your heart outside. I have this feeling. But sometimes I get confused living life, thinking real life is fake, unimportant—what's important is writing it out, summarizing it.

Actually looking back on my life, I was a talkative child. So I talk a lot, want to get my words out—that's what novels are written for. Next time I write I need to find another angle, say it all again. Slowly empty out all the words in my belly, then I'll feel settled in this life.

This is a praiseworthy peace: honest, clear, thoughtful. I congratulate you for publishing it. The extent to which he references Western writers is provocative. His idea that in 10,000 no one will speak Chinese is fascinating.