The man who told China’s story to the world—and the stories still left untold

A personal reflection and expert interview on memory, narrative, and China’s unfinished conversation with the world

Happy Dragon Boat Festival!

I attended a commemorative conference on the 120th anniversary of U.S. journalist Edgar Snow's birth on Friday at Peking University in Beijing. Co-organized by Peking University and the Xinhua Institute, the event was attended by Snow's relatives and close friends, as well as seasoned journalists and specialists on Edgar Snow studies and international communication.

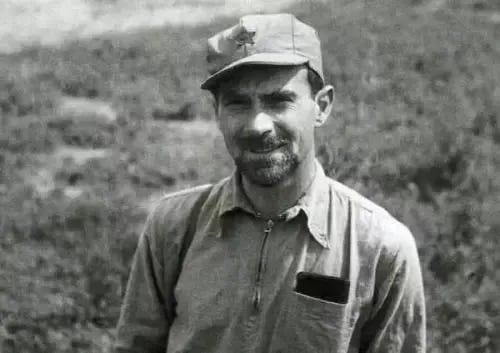

Edgar Snow holds a unique place in modern Chinese history as the first Western journalist to introduce China’s Red Army to the world. In 1936, at a time when China was embroiled in internal conflict and faced external aggression, Snow made his way to the remote headquarters of the Communist Party of China (CPC) in northwest China's Shaanxi Province, where he conducted extensive interviews with top Party leaders, including late Chinese leader Mao Zedong.

According to Xinhua News Agency, Snow's firsthand reporting culminated in "Red Star Over China," which was published a year later and provided not only the West but also China with a rare and authentic account of the Red Army, its leadership and its steadfast commitment to improving the lives of the Chinese people.

Snow also has a special connection to my family: the young bugler featured on the iconic cover of Snow's Red Star Over China was my uncle’s father, Xie Liquan. That photo was taken in September 1936 in Yuwangbao Town, Tongxin County, Ningxia, when Xie was just 19 years old.

In June that year, Snow had entered northwest China to interview the Red Army. He had been searching for a symbolic image that would show the Red Army as China’s vanguard against Japanese aggression. He was struck by the upright posture and sharp appearance of Xie —a young officer with a pistol at his side—and asked him to pose for what would become one of the most enduring images of the era.

A few years later, in 1940, Xie made his way to southern China, eventually becoming one of the commanders of the Pearl River Column, a key anti-Japanese guerrilla force in Guangdong Province. Under his leadership, the unit even supported operations by the World War II Allies in the Pacific theater.

That concludes the story of Xie. Now back to Friday’s event. Participants of the conference on Friday explored how China can build a more effective international communication system, with discussions focusing on themes such as "Presenting the real China to the World" and "Talent development & the legacy of Edgar Snow's spirit."

"Presenting the real China to the World" seminar held during the conference

Speaking at the conference's opening ceremony, Fu Hua, president of Xinhua News Agency, said that Snow was a sincere friend of the Chinese people, an envoy for China-U.S. relations, and a revered journalist.

"Through his cross-border, cross-cultural journalistic practice, Snow provided the world on both sides of the Pacific with an accurate, multi-dimensional and panoramic view of China," Fu said.

There’s no doubt that, nearly 90 years after Snow first came to China, the country still harbors a deep eagerness to be understood by the world. Attending the event, I found myself reflecting not only on the significance of Snow’s legacy, but also on the broader questions that surround it.

In Chinese discussions about Snow—his work, his visits, and his legacy—one phrase appears time and again: “the real China.” Back in the 1930s, very few outsiders had seen the Chinese Communist forces operating in northern Shaanxi. Snow’s Red Star Over China was groundbreaking precisely because it introduced a rarely glimpsed side of China to the world.

Now, nearly nine decades later, that desire hasn’t disappeared. If anything, it has evolved. You can still sense a strong eagerness—yes, that’s the word I’d use—among ordinary Chinese people to share their stories with the world. I’ve seen it firsthand, again and again. And today, just like back then, people continue to emphasize the need to show “the real China.” This persistent emphasis reveals something deeper: that an “unreal China,” or perhaps a misunderstood one, has never fully gone away. Even after all the profound transformations the country has undergone, this shadow still lingers. It’s no wonder, then, that so many Chinese people and a few international friends feel compelled to seize every opportunity to tell China’s story abroad. Some foreign media outlets have even picked up on this impulse itself, occasionally poking fun at how “hard” the Chinese government tries to promote its image.

Why has China not seen another figure quite like Edgar Snow? And what would it take for someone like him to emerge again? Of course, many people have followed in Snow’s footsteps. Some have written books, just as Snow did. Others livestream daily life in China to global audiences. In their own ways, each tries to show facets of China that are rarely visible abroad.

And yet, one wonders: why does China still commemorate Edgar Snow, after all these years?

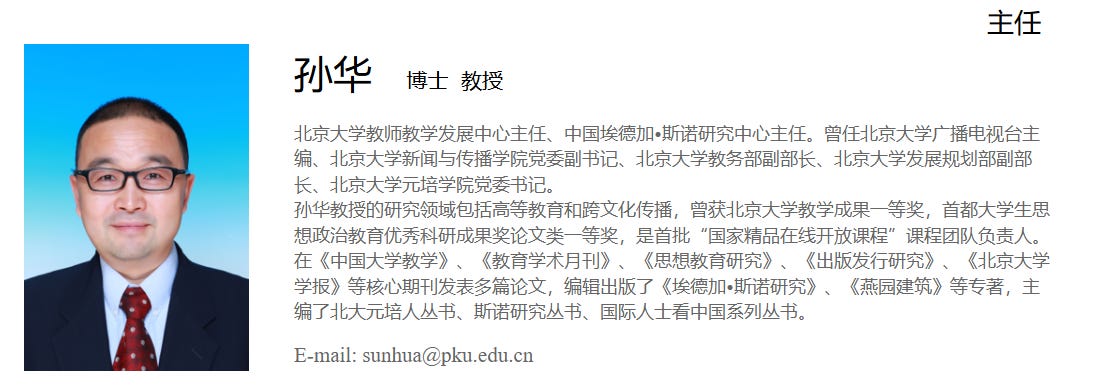

These were some of the questions on my mind when I sat down with Professor Sun Hua, director of Peking University’s China Center for Edgar Snow Studies (CCESS) during the conference. Here is our conversation.

Prof. Sun Hua, director of Peking University’s China Center for Edgar Snow Studies (CCESS)

JJ: In your view, what was the main reason for the world’s distorted or limited understanding of China during Snow’s time? And today, what misconceptions or misunderstandings about China dominate the international narrative?

Sun: Back in Snow’s era, one of the biggest reasons for the world’s ignorance about China was the strict media censorship imposed by the Kuomintang (KMT) government. The KMT didn’t want the outside world to know anything about the CPC or the Red Army. They went to great lengths to obscure the reality of the Communist movement.

In Red Star Over China, Snow mentioned that he arrived in northern Shaanxi with a list of 80 questions. He asked things like: What are the Red Army’s goals? What kind of ideology do they follow? Are their wives shared communally? Do they really carry crude bombs around their waists? Are they monstrous in appearance?

But what he found on the ground was strikingly different. In Yan’an, he saw Red Army members drinking coffee, playing the piano, and even playing tennis. He encountered many highly educated individuals who had returned from overseas and joined the Communist movement. He found them unusual—in a good way.

Snow was particularly struck by the Red Army’s "Three Main Rules of Discipline and Eight Points for Attention." That’s why John King Fairbank later said Snow had a kind of historical foresight—he saw that this group was capable of founding a new China. For example, the first of the Eight Points required soldiers not to stay inside villagers' homes while passing through but to borrow removable wooden doors to sleep on in the courtyards. Afterward, they would return and reinstall the doors before moving on. (“上门板”)

Another rule required that the army's toilets be placed far away from villagers' homes—simple, considerate acts. Over time, these values laid the groundwork for the Party’s political philosophy. Snow’s great contribution was that he pierced through the fog and revealed how this little-known army had truly won the support of the people.

Fast forward to today, and the dominant narrative in many parts of the world is that China’s rise is a threat. At the core of this, I think, is China’s lack of a robust, self-defined discourse system. The dominant global discourse is still shaped by Western media and institutions. Our macroeconomics, microeconomics—even journalism and law—are taught from foreign textbooks, based on Western frameworks.

But those frameworks often fail to explain what’s unique about China. That’s why we need to build a Chinese discourse system—one that can interpret and explain “Chinese modernization” on our own terms, so others can better understand what we’re trying to do.

JJ: Some overseas China watchers argue that the very act of building China's own discourse system challenges the existing Western one—or even threatens it. How do you respond to that concern?

Sun: There’s a traditional Chinese saying: “Harmony without uniformity” (和而不同). Every country has its own values, ethics, and ideologies. We respect that. But just as we don’t seek to replace others’ values with our own, we don’t wish for others to impose theirs on us.

As Fu Hua, president of Xinhua News Agency, said in his speech earlier today, we should “join hands to reach the radiant ‘far shore’ of mutual appreciation—where each country cherishes its own beauty and also values the beauty of others.” That’s the spirit we believe in.

JJ: Over the past 80-plus years since Snow, many international figures have helped introduce China to the world—people like Peter Hessler or even newer faces like IShowSpeed. One American that China holds in particularly high esteem is Henry Kissinger. Chinese media often wonder who might become “the next Kissinger” for China. It seems China has long hoped to find someone who can play a similar role—but no one has quite matched Snow or Kissinger’s historical impact. How do you view these “foreign friends” of China since Snow? Why do you think there hasn't been another figure on the same level?

Sun: I’ve read Peter Hessler’s books, and I think we should adopt a more inclusive attitude toward foreign friends. Some people say Snow was the first to report on the Long March, but actually, it was a British missionary named Rudolf Alfred Bosshardt (薄复礼) who encountered the Red Army during their march through China’s southwest borderlands.

Initially, the Red Army viewed missionaries as hostile, accusing them of spreading misleading ideas. But they soon saw how the missionaries helped treat villagers and decided to release them—except for Bosshardt, who stayed with the Red Army to help. They had an important French map that no one could read—except Bosshardt.

After the Red Army left the region, Bosshardt returned to Britain and wrote a book titled The Restraining Hand: Captivity for Christ in China. It contained many criticisms of the Party. But when the book’s Chinese edition was published years later, a Chinese general who had once detained him wrote a note in the preface. It said something like, “We welcome foreign critiques of China—especially those that are critical. They are the ones we must study most carefully.” I think that’s a profound and generous perspective.

So when people read Hessler’s River Town or other books and feel uncomfortable or offended—I would say, let these diverse voices exist. It’s precisely through that diversity that a fuller, more truthful image of China can emerge.

We shouldn’t expect every foreign friend to get everything 100% right, or to only say positive things about us. Even people at Peking University criticize the university—it often comes from a place of deep affection.

That’s why Lu Xun once said that Snow loved China more than some Chinese themselves. So I believe we need to be more open-minded, more tolerant of critical voices. If the criticism is valid, we should learn from it; if not, we can reflect and move on.

Also, I’d say Snow and Kissinger are fundamentally different figures. Snow stood with the Chinese people. He sympathized with their struggles. Kissinger, on the other hand, always approached China from the standpoint of U.S. national interest. His belief was that maintaining good relations with China would benefit America.

Snow, however, operated from a deeply personal place. He broke through ideological, cultural, and religious barriers to truly understand China. That’s what we mean by “harmony without uniformity.” Only through mutual appreciation can we move toward a more harmonious world.

JJ: Suppose an ordinary American who’s never heard of Edgar Snow asks you: Why is China still commemorating him, even on the 120th anniversary of his birth? What would you say?

Sun: This year marks the 80th anniversary of the victory in the Chinese People’s War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression and the World Anti-Fascist War. Snow’s Red Star Over China played a key role in introducing played a crucial role in introducing the CPC's idea of forming a united front against Japanese aggression. Thanks to Snow’s reporting, U.S. delegations—including military observers—traveled to northern Shaanxi to support China’s anti-fascist cause. Mao Zedong once said, during an interview with a German journalist, that “when the whole world had forgotten about us, only Snow came.” That’s why we will never forget the immense contribution he made.

The Chinese people are quite nostalgic. We do not forget old friends. We do not forget those who stood by us during difficult times. And this moment—this anniversary—is an opportunity. Figures like Snow, who live in the shared memory of both Chinese and American people, can help bridge the distance between our nations.

Shi Yifei, Wei Mengjia, and Liu Jiani also contributed to today’s newsletter.

Thanks, incredible story.