Tracing China’s historical practice of sovereignty over the South China Sea Islands

Insights from Liu Yanhua, associate research fellow of the National Institute for South China Sea Studies

An exhibition exploring China’s resumption of sovereignty over Taiwan and the Nanhai Zhudao, or the islands in the South China Sea, opened in Nanjing University, on Monday. Among hundreds of historical materials on display are a series of historical maps tracing China’s governance and cartographic records of the Nanhai Zhudao — known as the South China Sea islands in English.

Liu Yanhua, an associate research fellow at the National Institute for South China Sea Studies, highlighted several of these maps in an article published Tuesday on the institute’s WeChat blog. Today’s piece is a translation of the main points of Liu’s article by Jiang Jiang, Xia Tian and Wang Xiaopeng.

In this piece, Liu noted that

中国拥有南海诸岛主权建立于长期的历史实践中,具有发现、命名、开发利用、行政管辖的完整证据链条。但是,早期西方国家“获得”主权的方式却带有浓厚的殖民色彩,往往是来到一块“未知”土地、插旗鸣炮就“获得”主权,这种主权获得是建立在漠视原住民权利的基础之上,也让英国、法国、日本尽管在南海诸岛见到驻岛生产的中国渔民,仍将其视为“无主地”。

China’s sovereignty over the Nanhai Zhudao was established through a long course of historical practice, supported by a complete chain of evidence covering discovery, naming, development and utilization, and administrative jurisdiction. By contrast, the ways in which early Western powers “acquired” sovereignty were deeply colored by colonialism. Typically, they would arrive at a so-called “unknown” land, plant a flag, fire ceremonial shots, and claim sovereignty — a process that disregarded the rights of indigenous peoples. As a result, even when British, French or Japanese explorers encountered Chinese fishermen living and working on the islands, they still regarded the Nanhai Zhudao as terra nullius, or land belonging to no one.

Liu then gave an example: In 1947, when France sought arbitration with China over sovereignty of the Xisha Islands, Qiu Zuming, then First Secretary and Acting Chargé d’Affaires of the Chinese Embassy in Turkey, noted in reference to China’s traditional mode of territorial administration:

“按照国际公法,无主荒地之占领,依照占领时之国际法规,我国将该岛划归粤省管辖时,远在国际法成为专书之前,只有渔人前往,自无设官之必要。”

“According to international law, the occupation of terra nullius should be judged in light of the legal norms in effect at the time of occupation. When China placed the islands under the jurisdiction of Guangdong Province, it was long before international law had been systematized. At that time, only fishermen went there, and therefore there was no need to establish official administration.”

Such differences in legal concepts and practices concerning territorial sovereignty, in effect, provided Western countries with a pretext for encroaching upon China’s sovereignty over the Nanhai Zhudao, said Liu. Recognizing the harm caused by these differences, the Chinese government later adopted approaches in line with international norms to reaffirm its sovereignty.

For example, Li Zhun’s patrol of the Xisha Islands was acknowledged by the Western world — though in their eyes, his patrol was seen as an “occupation” rather than an assertion of sovereignty over China’s own territory.

In 1909, Li Zhun, commander of the Guangdong Fleet of the Qing Dynasty, conducted the first official inspection of the Xisha Islands on behalf of the Chinese government, proclaiming the islands as Chinese territory.

In the article, Liu introduced maps that included those published by China in 1935 concerning the South China Sea. These maps represented the efforts of the then Republic of China (ROC) government to assert China’s sovereignty over the region. Liu noted that such efforts have been deliberately downplayed — for instance, the Wikipedia entry on the “Spratly Islands Dispute” claims that China only began asserting sovereignty over the Nansha and Xisha Islands after drawing the nine-dash line map in 1947.

The maps in 1935 were worked out as numerous errors and inconsistencies were found in maps published in China at the time, particularly regarding national boundaries, according to the first issue of the Journal of the Commission for the Examination of Land and Water Maps. To address this, the then Ministry of the Interior convened an inter-ministerial meeting in 1930 to discuss and formulate rules for the examination of land and water maps, and in 1933, the Commission for the Examination of Land and Water Maps (“水陆地图审查委员会”) was officially established. Each participating ministry assumed specific responsibilities — the Ministry of the Interior was in charge of reviewing administrative divisions and related matters, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs was responsible for boundaries and treaty-related territories, while the Ministry of Education oversaw academic terminology, historical evolution, meteorology, and the intended uses of the maps.

From its establishment on June 7, 1933, to the end of December 1934, this commission held a total of 26 meetings. At its 25th meeting on December 21, 1934, the commission approved a list of 172 Chinese and English names for islands in the South China Sea. These names were published in the first issue of the Journal of the Commission for the Examination of Land and Water Maps in January 1935, followed by the publication of the Map of the Islands in the South China Sea of China in the second issue in April that year.

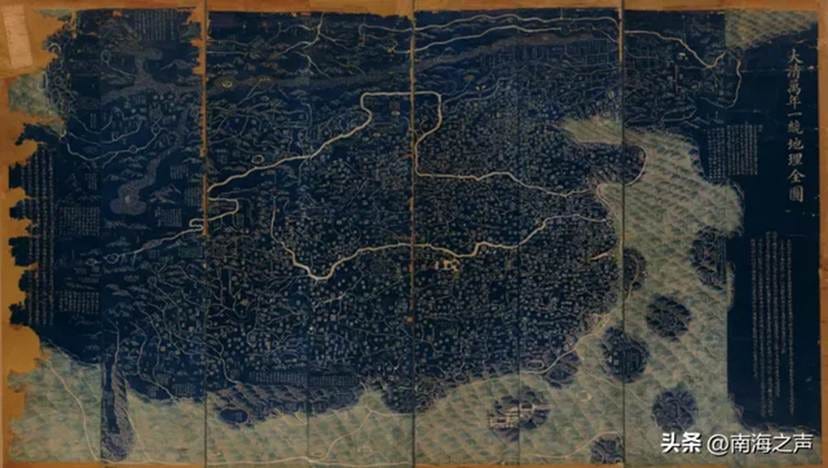

The compilation of these maps was deeply rooted in China’s long-standing historical practice of exercising sovereignty over the Nanhai Zhudao. From a cartographic perspective, it continued the tradition of depicting the South China Sea islands —historically referred to as “Changsha” and “Shitang” since the Ming and Qing dynasties — on territorial maps such as the Complete Map of the Everlasting Unified Great Qing Empire. The depiction of the Nanhai Zhudao thus evolved from collective references to more detailed representations of individual islands, reefs, and shoals. Subsequent Chinese maps followed this model, marking both the extent of the Nanhai Zhudao and the names of their features.

Created in the 15th year of the Jiaqing reign (1810) during the Qing Dynasty, the map is printed in two colors on paper, composed of 24 joined sheets, with the artist unspecified. (This map was shown in the exhibition)

Liu said that the effort to explain China to the international community in ways accepted by Western audiences took shape in various aspects of modern Chinese history. A group of Chinese scholars well-versed in both Chinese and Western learning undertook this important task.

To “meet the long-felt needs of English readers,” The Chinese Year Book 1935–1936 was published by the Commercial Press in Shanghai in 1935. Unlike The China Year Book, edited by British scholar H.G.W. Woodhead since 1921, this was the first English-language Chinese Year Book written entirely by Chinese editors and scholars.

According to Liu, the yearbook contained 45 chapters covering subjects such as history, geography, climate, population, the military, industry, culture, religion, and government institutions. Its contributors included leading Chinese scholars of the time, such as Gu Jiegang, Zhu Kezhen, Wang Shijie, and Weng Wenhao. Publication of The Chinese Year Book continued in different locations after China started a whole-of-nation resistance against Japanese aggression in July 1937.

Beginning with the 1938–1939 edition, the English-language Chinese Year Book took on the mission of presenting China’s war efforts to the world. In the foreword to that edition, Xu Shuxi, then Director of the Commission for International Affairs, wrote that this was a “war issue,” with three-fourths of its content devoted to the war and related matters. “Just as the 1937 edition bore testimony to the achievements of reconstruction under the National Government before Japan’s destruction of it,” Xu wrote, “we hope this volume will serve as a record for posterity — of how the Chinese people, against great odds, heroically defended their nation and the civilization they share with the rest of the world, including the aggressors themselves.”

The Map of China compiled for the English-language Chinese Year Book vividly demonstrated the Chinese people’s determination to safeguard their territorial sovereignty. In the 1936–1937 edition, the Map of China was published as a separate supplement, said Liu. It featured a brick-red hardcover with the title MAP OF CHINA and the note “Drawn Specially for the Chinese Year Book by Sheng-tsu Wang.”

Wang Shengzu, one of China’s earliest geographers to study in the United States, obtained a master’s degree in geography from the University of Chicago in 1929. Upon returning to China, he taught at Tsinghua University and other institutions. His research combined a national perspective with an international outlook, and his strong command of English likely made him the ideal author for the English version of the Map of China. In the same edition, Wang also wrote the section on “Northeast China,” which systematically described Japan’s military invasion, economic plunder, and colonial rule in the region.

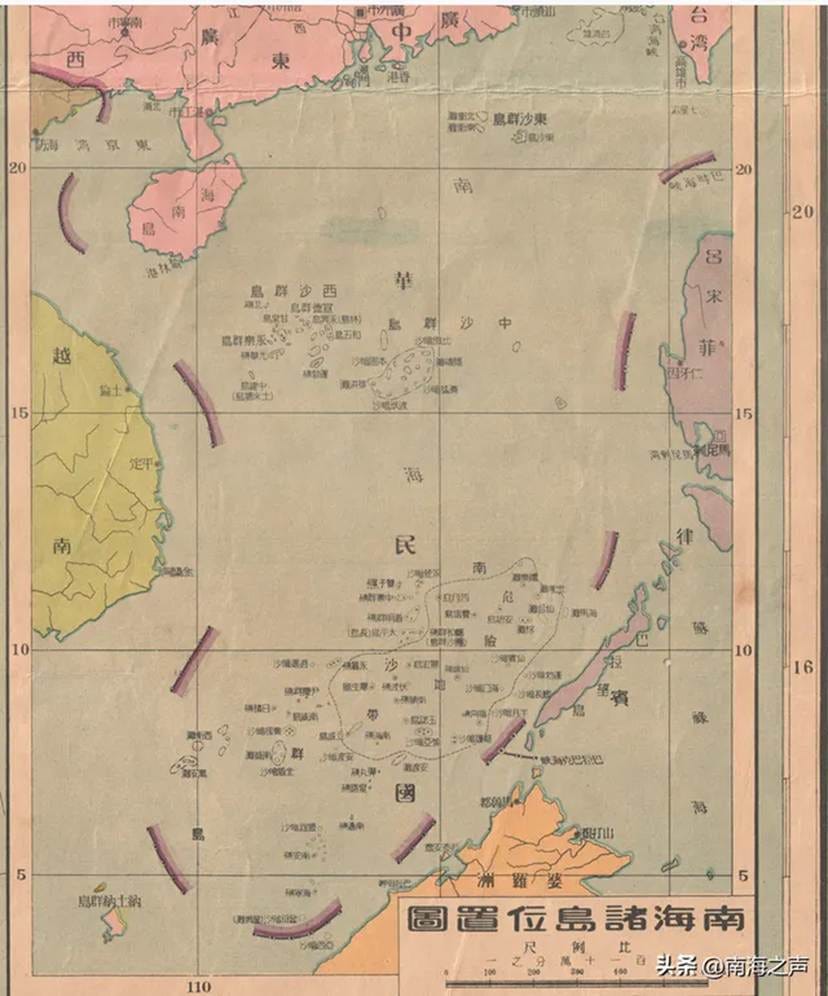

In the MAP OF CHINA, the lower-right corner featured a boxed inset labeled “South China Sea.” The area was shaded in the same color as the Chinese mainland, with the islands marked and named in accordance with the official designations published by China in 1935 — serving as an English-language presentation of China’s sovereignty claims over the Nanhai Zhudao. The 1938–1939 edition also carried an updated English version of the Map of China, copies of which are still preserved in libraries in the United States, Canada, and elsewhere.

In November 1937, to strengthen international communication and win foreign support, the National Government established the International Information Division under its Central Headquarters, led by Dong Xianguang, a prominent journalist educated in the United States. The division had a Compilation Section responsible for foreign-language publications. From February 1938, it was placed under the Central Publicity Department, with an overseas office established in New York — then a key hub for international publicity — and branches in London and other cities.

According to incomplete statistics, during the war years the division published over 290 foreign-language periodicals exposing Japanese atrocities and publicizing China’s war efforts and major political figures. It also distributed more than 11,000 publicity photographs abroad, including to Japan. This indicates that the 1938–1939 edition of The Chinese Year Book was likely promoted through this external publicity network, giving it broad international circulation and readership. Alongside China’s resistance narrative, the publication also conveyed China’s claims of sovereignty over the South China Sea islands.

After 14 years of arduous struggle, China achieved victory in 1945, recovering all territories seized by Japan, including the South China Sea islands.

In February 1948, the Chinese government (ROC) officially published the Administrative Map of the ROC. The map included an inset titled Location Map of the South China Sea Islands. (This map was shown in the exhibition)

In 1947, when the Ministry of the Interior and other departments convened to discuss the scope of the South China Sea islands, they reaffirmed the boundaries announced in 1935: “The southernmost extent of China’s South China Sea territory reaches Zengmu Shoal. Before the war, this demarcation had been consistently used by government agencies, schools, and publishers, and had been formally filed with the Ministry of the Interior. The original record remains unchanged.”

At the end of the article, Liu concluded that China’s sovereignty claims over the Nanhai Zhudao thus continued to gain international recognition after the war, supported by its renewed administrative and developmental activities over the islands.